The Ukraine - Russia Cyberwar: Everything You Need to Know

- The Buildup to the Cyberwar in Ukraine

- Why Does Russia Use Cyberwar?

- Who’s Involved?

- What Are the Most Significant Cyberattacks Since 2014?

- What Russian Cyberattacks Occured Pre-Invasion?

- Any Russian-Linked Cyberattacks During the Invasion?

- What’s Ukraine’s Response?

- Are People Profiting from Cyberattacks?

- What Are the Risks of Cyberwarfare?

- How to Protect Yourself?

- The Bottom Line

Russia may have moved troops into Ukraine on February 24th, 2022, but its cyberwar against Ukraine began eight years earlier. Long before Putin’s full-scale invasion, Russian hackers began targeting Ukrainian infrastructure and government institutions.

Because the cyberwar is an important but hidden element of this campaign, we’ve gathered as much data as we can to update you on this side of the conflict. We’ll cover significant cyberattacks, cyber’s role in the current conflict, and steps you can take to stay safe.

We’ll also update this article as the situation in Ukraine develops so those affected know what’s happening with their data.

The Buildup to the Cyberwar in Ukraine

Since Putin first came to power in 2000, Russian diplomatic relations with former Soviet republics have been marked by Russian aggression and disinformation. He has described the dissolution of the Soviet Union as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century,”¹ and talks openly about rebuilding the Soviet Union.²

This began in 1999 with the Second Chechen War, before Putin was even formally elected President of Russia. In that campaign, in a way that foreshadows what’s happening today in Ukraine, Putin declared the Chechen President’s authority illegitimate and, in a series of increasingly aggressive moves that belied his stated intentions, took control of the country, which is now part of Russia.

Putin used similar tactics of disinformation and cyber warfare in Russia’s 2014 campaign against the Crimea, a formerly Ukrainian territory located along the northern coast of the Black Sea. In the Russian annexation of Crimea, Putin dissolved Crimean press, used state sponsored media as well as social media to spread lies about fascism in Ukraine, and used troops disguised as separatists to overtake the Crimean parliament.

When Russia formally moved troops into Crimea, its stated intention was to protect Russians and “normalize” the situation.

Following the 2014 annexation of Crimea, brutal and bloody conflict has raged in eastern Ukraine between Russian-backed separatist forces and the Ukrainian military. At the same time, Russian cyberattacks against Ukraine have escalated, focusing on Ukrainian hospitals, energy systems, government institutions, and websites. This is all in an apparent effort to destabilize Ukrainian politics, aid the spread of disinformation, and affect the Ukrainian military.

Ukraine has responded with cyberattacks of its own, targeting Russian military forces, disinformation campaigns, and intelligence agencies. However, the economic disparity between the two nations puts Ukraine at a disadvantage.

Cyberwarfare between the two nations further escalated in late February, 2022, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Following the same playbook Russia used in Chechnya and Crimea, Russian hackers and news outlets are spreading disinformation to build a pro-Russian justification for the invasion.

Putin has falsely claimed that Ukraine is a fascist government committing genocide on its own people. And his disinformation campaign is extremely effective in Russia. Reports have even emerged of Russian citizens refusing to believe images that show Russian aggression in Ukraine.³ Russian cyber tactics are also designed to disrupt Ukrainian defensive efforts, communication channels, and civilian infrastructure.

And Russia is a master of cyberwarfare. According to Rolf Mowatt-Larsen, a former chief of the CIA’s Moscow station, it’s part of “Putin’s playbook.” Speaking to USA Today, Mowatt-Larsen warned, “The whole world is now getting introduced to the idea of hybrid war.”

Analysts warn that Russian hackers could disable Ukrainian infrastructure completely to help the Russian advance on Kyiv. According to Mowatt-Larssen, "[Putin] could turn out the lights in Ukraine before it even knows what’s happening.”

Since he first came to power, Putin has expressed concern over the continued eastward expansion of countries joining NATO, and has in particular forbidden NATO to include Ukraine as a member nation.

He has also expressed his desire to return Russia to the former glory of the Soviet Union. He sees Ukraine as important to achieving that glory, and he has shown that he is willing to use cyberwarfare and disinformation, and to break international law, to bring Ukraine back into the Soviet fold.

With the Russian invasion, Ukraine’s Vice Prime Minister and Minister of Digital Transformation, Mykhailo Fedorov, has called on volunteers to join the “IT Army,” a cyber force created to repel Russian cyberattacks and disinformation, as well as to attack Russian infrastructure. And Western nations and big-tech institutions have hit Russia with some of the hardest economic sanctions in history, and imposed measures to limit Russia’s disinformation campaign.

In response, Putin’s rhetoric has grown more threatening and erratic, and analysts fear Russian cyberattacks could spread beyond the Russia-Ukraine conflict to target Western nations. If that happens, it could lead to cyber warfare on a global scale.

Why Does Russia Use Cyberwar?

Russia has used cyberwar to accomplish a number of its objectives, both in Ukraine and elsewhere. Between 2014 and 2022, Russia launched a number of cyberattacks designed to disrupt Ukraine’s government institutions and influence the nation’s foreign policy.

Cyberattacks on energy infrastructure caused major power outages across Ukraine in 2015 and 2016. Speaking to Slate, cyberwar author and Wired writer Andy Greenberg said these attacks were designed to make Ukrainian citizens feel vulnerable.

“These cyberattacks were a way to send a message to the rest of Ukraine that you too are vulnerable. Even though you’re hundreds of miles away from the fronts, we can reach you, too. You’re all subject to our sphere of influence.”⁴

Russian disinformation campaigns continued to spread pro-Russian and anti-Ukrainian propaganda for several years. Russia also used cyber operations in Ukraine as training exercises to develop its capabilities.

Russia has adopted similar hacking methods outside of Ukraine, often targeting influential Western governments like the US, the UK, and Germany. In 2014, Russia used cyber tactics to disrupt the Ukrainian Presidential Election. And in 2016, Russia ran a similar disinformation campaign against the United States’ Presidential Election.

Russian attacks on elections continue to undermine the democratic process in Western nations, including the theft of sensitive intelligence data. For example, in 2016, Germany’s domestic intelligence agency claimed Russian hackers attacked state computers. And in 2020, the CIA blamed Russian state-sponsored actors for a breach of the US Federal Government.

In 2022, cyberattacks have been used to create fear and confusion in Ukraine. To “prepare the battlefield”⁴ according to Greenberg. Speaking to Slate, Greenberg also outlined how Russian cyber tactics have shifted during the physical invasion:

“Cyberattacks have been designed to prepare the battleground in the sense of creating confusion as Ukraine tries to figure out what is going on, to scare people. But then once the physical invasion starts, it is more tactical accompaniments of physical war.”⁴

Who’s Involved?

Several hacking groups and nation-states are acting on behalf of Russian and Ukrainian forces following the Russian invasion.

Pro-Russian Hacking Groups

In Russia, three major intelligence agencies account for much of the government’s cyber activities: The Federal Security Service⁵ (a domestic security agency), the Foreign Intelligence Service⁶ (an external intelligence agency), and the GRU⁷ (a military intelligence agency).

The GRU is of particular interest. Most of Russia’s disruptive state-sponsored hacking operations come from the GRU and its infamous hacking groups are extremely proficient.

Unit 26165 is responsible for several high-profile cyberattacks in recent years. Also known as Fancy Bear (or APT28), the group was behind the 2014 cyberattacks on the Ukrainian election and the 2016 US Presidential Election hacks.

Unit 74455 is another hacking group in the GRU. Also known as Voodoo Bear or Sandworm, this group is responsible for the NotPeyta hacks in 2017, which caused billions of dollars worth of damage globally.

Speaking to Slate, Greenberg calls Sandworm the most active cyberwarfare hacker group in the world. “This is a group that specializes in just inflicting maximum chaos globally.”

Other hacking groups are supporting Russia’s invasion. UNC1151 (or Ghostwriter) has attacked Ukrainian websites. Ghostwriter has sophisticated capabilities and acts on behalf of the Belarussian government. Conti is another group openly supporting the Russian invasion.

Pro-Ukrainian Hacking Groups

Russian cyber capabilities outgun Ukraine’s, but over the last six years, the Ukrainian Cyber Alliance (UCA) has helped the Ukrainian government repel Russian hackers. Several hacktivist groups merged to form the UCA, which is responsible for the Surkov Leaks among others.

In February, 2022, Ukraine’s Vice Prime Minister and Minister of Digital Transformation, Mykhailo Fedorov, asked for volunteers to join the “IT Army,” a cyber team of civilian hackers designed to counter Russian hacking. “We are creating an IT army. We need digital talents,” wrote Fedorov in a Twitter post. So far 230,000+ people have joined, with Russian websites, banks, and energy the group’s primary targets.

Fedorov appealed to “digital talents” in a Twitter post on Feb. 26th

Fedorov appealed to “digital talents” in a Twitter post on Feb. 26th

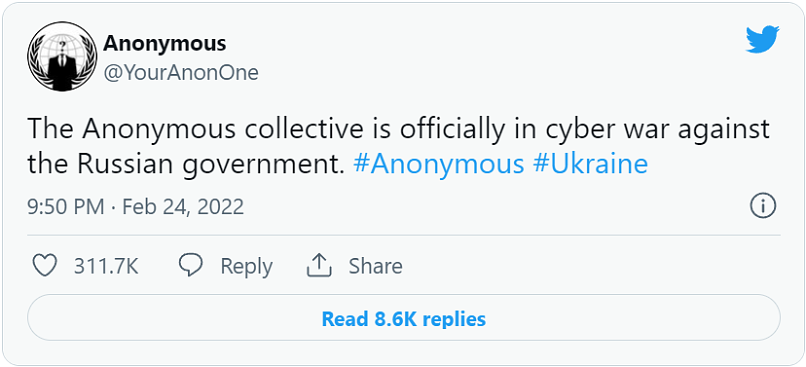

Hackers from around the world have also rallied in support of Ukraine, including the decentralized hacking collective known as Anonymous. The members of Anonymous operate individually under the Anonymous name, and the hacktivist collective has been responsible for a number of high-profile cyberattacks going back to 2003. Their activity stalled after a series of high-profile arrests in the 2010’s, but resurged following the murder of George Floyd in 2020.

And in late February 2022, Anonymous declared cyberwar on Russia. The group already claims to have successfully attacked Russia’s Ministry of Defense.

Anonymous pledged support for Ukraine following Russia’s invasion.

Anonymous pledged support for Ukraine following Russia’s invasion.

Ghostsec, a group many people believe to be an offshoot of Anonymous, is also supporting Ukraine. Ghostsec was initially involved in countering religious extremism websites belonging to ISIS.

AgainstTheWest (ATW) is allegedly attacking Russian infrastructure, while SHDWsec is working with ATW and Anonymous on behalf of Ukraine.

Another hacktivist group called the Belarussian Cyber Partisans has already hacked Belarussian rail systems to slow down troop movements, and Raidforums Admin is attacking Russian websites and infrastructure.

KelvinSecurity, meanwhile, is tweeting evidence of hacking against Russian targets, and new groups are continually pledging support for Ukraine.

What Are the Most Significant Cyberattacks Since 2014?

The Russia-Ukraine cyberwar is characterized by major Russian operations and Ukrainian retaliation.

Russian cyberattacks have often sought to inflict the maximum level of chaos and disruption.

Ukraine’s cyber response has countered Russian disinformation campaigns, disrupted Russian communication, and conducted cyberespionage operations against opposing military forces.

What Russian Cyberattacks Occured Pre-Invasion?

Russian cyberattacks have increased significantly since negotiations broke down between Russia and NATO in mid-January, 2022.

Russia increased its cyber activities just one day after their NATO proposal hit a dead-end. Hackers compromised Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Education Ministry websites to display ominous messages on-screen like “Ukrainians … be afraid and expect worse.”

The attack also crippled Ukraine’s Diia service and several other government websites. Diia allows Ukrainian citizens to access important digital documents and over 50 government services. Russian hackers enacted these attacks to destabilize Ukrainian infrastructure and spread fear across the country. Since January, Russia has spread disinformation and attacked Ukrainian infrastructure in preparation for a full-scale military invasion.

Disinformation

From creating fake social media accounts and spreading pro-Trump materials during the 2016 US election, to continuing Russian propaganda in Ukraine, disinformation tactics have been a significant part of the Kremlin’s foreign policy toolbox under Putin.

The Russian government is willing to go to extreme lengths in its disinformation campaigns, embedding itself in extremist groups, hacking sources of information, and building narratives over the course of several years.

For months before the invasion, Putin sought to characterize Ukraine as a security threat to Russia. Social media accounts posted viral content suggesting Ukraine is a fascist and tyrannical state subjecting people to genocide. Many of these accounts also characterize Ukraine as a puppet of the West.

Unsourced videos emerged of civilian evacuations in the separatist-controlled area in eastern Ukraine. Despite this apparent state of emergency, the video’s metadata showed it was recorded three days before being released. A rebel guard station is blown up in one video, and another allegedly shows Ukrainian agents under arrest. The videos implied Ukrainian forces were committing war crimes, though US intelligence did highlight the possibility of Russia using phony videos as a pretext to war¹⁹.

Some sources have even suggested Putin’s speech, released before the invasion, was pre-recorded. In this public announcement, Putin justified the invasion with claims Russia could no longer feel "safe, develop and exist"²⁰ because of Ukraine.

Putin also claimed the Ukrainian government was responsible for genocide in separatist regions. He said Russia is launching a “special military operation”²⁰ to “demilitarize and denazify Ukraine.”²⁰ That Ukraine’s president is Jewish would appear to undermine any claims of the Ukrainian government being Nazi. But Putin is willing to double-down on disinformation, even when presented with compelling evidence that says otherwise.

Putin’s falsified claims also represent a shift in the Kremlin’s disinformation strategy. Instead of spreading disinformation through social media accounts, official government communications and state-backed media corporations are now the preferred methods.

According to Samuel Charap, a senior member of RAND corporation speaking to USA Today, Russia uses disinformation to create “a narrative to sell to the Russian public and the world about why whatever action Russia takes is ultimately justified."²¹

DDOS Attacks

Part of Putin’s cyber arsenal are “distributed denial of service” (DDoS) attacks. DDoS attacks occur when multiple devices simultaneously send loads of data to a computer network. DDoS attacks are meant to overwhelm and disable computer networks.

Russia conducted several DDoS attacks on Ukrainian websites and financial institutions leading up to the Russian invasion — attacks designed to disable Ukrainian infrastructure and cause panic across the country.

One attack targeted several Ukrainian websites in mid-February, including Ukraine's Ministry of Defense and two of its largest banks, PrivatBank and JSC Oschadbank. The attacks affected online payments and banking apps, and Russia supplemented these hacks with disinformation that claimed ATMs had stopped working. U.S. and U.K. officials blamed the attacks on the GRU.

One day before the Russian invasion, hackers DDoS attacked several important government websites, including the Ministry of Defense, Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Security Service (SBU), and Cabinet of Ministers.

Malware Attacks

In addition to DDoS attacks, Russia also makes heavy use of malicious software (malware). On February 23rd, 2022, Russian hackers used a new strain of malware called “HermeticWiper” against Ukraine.

HermeticWiper malware is used to delete data from computer systems. This particular strain also stops computers from rebooting. The malware attack affected over 100 machines across Ukraine’s financial, defense, aviation, and IT sectors before being detected. The HermeticWiper also spread to Lithuania and Latvia.

We’ve also seen unconfirmed reports of Russian phishing attacks, which targeted Ukrainian citizens with malware that was hidden in email attachments. According to the SSSCIP Ukraine’s Twitter account, attackers were trying to gather information from Ukrainian citizens’ mobile phones.

Any Russian-Linked Cyberattacks During the Invasion?

Since Russian forces invaded on February 24th, 2022, their hackers have carried out further cyberattacks on Ukraine’s digital infrastructure. Primarily, Russian attacks focus on disrupting communication channels and sources of information.

Russian cyberattacks haven’t represented the intense, mass-scale cyberwarfare many people expected. Analysts have speculated that Russia is now adopting a more cost-effective cyber strategy.²¹ That being said, data suggests Russian cyber activity is spiking in Ukraine.

Significant Russian-linked cyberattacks since the start of the Russia-Ukraine conflict include:

- Feb. 24th, 2022: Attack on Kharkiv’s Internet

Cybersecurity watchdog NetBlocks notes massive disruption to web service in Kharkiv, Ukraine, one of the focal points of Russia’s military offensive. Around one-quarter of users suffer a loss of connection in the city and its surrounding region.

- Feb. 24th, 2022: Attacks on the Kyiv Post

One of Ukraine’s biggest media outlets, the Kyiv Post, is constantly attacked on the first day of the invasion. Russia’s attack on information sources is designed to create confusion and further Russia’s disinformation campaign.

- Feb. 25th, 2022: Ukraine Border Control Hack

A Ukrainian border control station is infected with data-wiper malware. The cyberattack significantly affects the station's ability to process refugees crossing into Romania.

- Feb. 28th, 2022: Foxblade Trojan Attacks

Trojan malware targets Ukraine’s digital infrastructure and ultimately affects several sectors, including financial, agricultural, energy, emergency services, and humanitarian aid. Hackers steal health, insurance, and transport-related personally identifiable information (PII) as well as government data. Hackers also disrupt civilian infrastructure and spread disinformation.

What’s Ukraine’s Response?

Pro-Ukrainian hackers are using cyber tactics to push information about Russian aggression to the Russian population. This is meant to counter Russian disinformation. Pro-Ukrainian hackers are also attacking Russian domains that are important for military coordination, including hacks on email servers, and Ukrainian hackers are trying to exfiltrate military intelligence in cyberespionage operations.

Ukraine lacks the cyber capabilities to resist Russian hacking on its own. Ukraine’s initial response was to gather support, both from its own population and from independent groups like Anonymous, to counter Russian cyberattacks and disinformation.

The IT Army

As mentioned, over 230,000 civilians have joined Ukraine’s new “IT Army,” and several high-profile hacking collectives are supporting Ukraine.

The IT Army comprises a defensive unit and an offensive unit, each with different strategic objectives. The defensive unit protects Ukraine’s critical infrastructure from Russian hackers, including energy systems and banks. The offensive unit cyberattacks Russian targets and conducts espionage to help Ukraine’s military.

The IT army claims it has successfully attacked several Russian websites and a major Russian bank, Sberbank. The group is also distributing factual information in Belarus to counter Russia’s disinformation campaign.

Ukrainian Twitter accounts are involved in “meme warfare” to a similar effect. These accounts satirize President Putin and Russia with political cartoons and jokes.

The IT Army is moving beyond attacks on Russian websites to target Russian infrastructure. On February 26th, the IT Army’s Twitter account took responsibility for attacking Russia’s e-governance portal. Attackers also disabled websites for Russian aerospace and railroad companies.

Hacking Groups Attack Russian Institutions

Anonymous and Ghostsec have also combatted Russian aggression with attacks on Russian institutions. Anonymous claimed responsibility for a cyberattack on Russia’s Ministry of Defense on February 25th, 2022. Hackers leaked thousands of emails, passwords, and phone numbers belonging to Russian officials.

Attacks have targeted sources of Russian disinformation. Anonymous hackers disabled the state-backed news website Russia Today with DDoS attacks. They also hacked Russian state TV channels to display pro-Ukrainian content, including patriotic songs and images of the Russian invasion. Anonymous further claims to have breached a Russian space agency. Elsewhere, Ghostsec has allegedly stolen a trove of data from the Russian Information Office.

The Belarus Cyber Partisans breached systems that control Belarussian trains, bringing them to a halt and disrupting the movement of Russian soldiers into Ukraine. And we can expect more sophisticated attacks on Russian infrastructure as the Russia-Ukraine conflict continues.

According to recent statistics, Russian organizations are facing an increased cyber threat.

Big Tech’s Response

Big tech has also acted fast to impose their own “digital sanctions” on Russian media accounts, disinformation outlets, and payment services.

Ukraine’s Digital Transformation Minister, Mykhailo Fedorov, personally appealed for “support”²³ from Apple chief Tim Cook during the initial stages of Russia’s invasion:

"In 2022, modern technology is perhaps the best answer to the tanks, multiple-rocket launchers and missiles,"²³ Fedorov wrote.

Fedorov also asked Meta to remove Instagram and Facebook in Russia. However, the company responded that its platforms could be used to "protest and organize against the war and as a source of independent information."²⁴

Big tech’s response has centered around limiting Russian disinformation. Microsoft and Apple removed Russia Today’s media apps from marketplaces, and several platforms have severed Russian-backed media’s access to advertising revenue. These include Youtube and Google, which blocked Russian media from using its advertising tools.

Social media platforms are taking a similar approach to Russian media outlets, but Twitter and Facebook are also acting against Russian disinformation accounts.

Twitter claims it is “actively monitoring”²⁵ its platform for risks. Meanwhile, Facebook has intercepted information warfare groups posing as various fake personas and news outlets.

Big tech companies have adopted other measures to protect users physically. Google announced it was disabling features in Ukraine that detail live traffic information and the number of people in public locations. Facebook sent Russian users a notification about account security and restricted viewing and searching accounts’ friend lists.

Russia’s communication regulations agency, Roskomnadzor, responded angrily to Facebook, claiming the company is "violating the rights and freedoms of Russian citizens"²⁶ with its controls on Russian media.

A Timeline of Cyberattacks on Russia Since the Invasion

Here’s a timeline of cyberattacks we witnessed/read about on Russian companies, media outlets, and government organizations since Russia invaded Ukraine.

Feb. 24th, 2022

- Anonymous agents “declare war” on Vladimir Putin.

Feb. 25th, 2022

- Russian oil company Gazprom is cyberattacked, disabling its website.

Feb. 25th, 2022

- Several Russian government websites are disabled in DDoS attacks, including the Ministry of Defense’s website.

- Anonymous exfiltrates emails from a Russian Ministry of Defense database.

- (Rumored) Anonymous agents leak critical information about the Russian paramilitary (the VDV) and hand details to intelligence agencies.

Feb. 26th, 2022.

- The Georgian Hackers Society attacks Russia’s largest bank, Sberbank, via an SQL vulnerability.

- Russian government websites are cyberattacked again.

- Anonymous leaks 200GB of emails from Belarusian arms manufacturer Tetraedr.

Feb. 27th, 2022

- Anonymous agents hack Russian TV to display pro-Ukrainian content.

- An Anonymous splinter group sends a message to Putin.

- An Anonymous-affiliated account posts a video showing how to bypass Russian censorship.

- Unaffiliated hackers take control of a SCADA system belonging to Russian gas company FORNOVOGAS. SCADA systems manage data from industrial equipment.

Feb. 28th, 2022

- Meta (Facebook) removes a Russian disinformation network.

- Hackers attack the state-backed media group Russia Today.

- Hackers change the callsigns for several yachts to “FCKPTN.”

- Russian E.V. charging stations are disabled and display the text: “PUTIN IS A DICKHEAD.”

- Anonymous-affiliated account asks people to tell Russians about the conflict in Google Maps reviews of Russian businesses

- The Georgian Hacker Society disabled the Russian train system.

- More Russian news channels are hacked to show anti-Putin propaganda.

- Anonymous agents disable several Belarusian government websites, including:

•The Ministry of Communications and Informatization of the Republic of Belarus (mpt.gov.b)

•The State Authority for Military Industry of the Republic of Belarus (vpk.gov.by)

•The Belarusian military (mil.by) - Anonymous agents disable numerous Russian government websites, including:

•ria.ru (state media)

•rkn.gov.ru (restored and back online)

•www.gov.ru

•data.gov.ru

•ach.gov.ru

•svr.gov.ru

•fss.gov.ru

•edu.gov.ru

•sev.gov.ru

•open.gov.ru

•odkb.gov.ru

•scrf.gov.ru

•fso.gov.ru

•duma.gov.ru

•fms.gov.ru

•gov.rkomi.ru

•fmba.gov.ru

•pravo.gov.ru

•minenergo.gov.ru

•regulation.gov.ru

•premier.gov.ru

•sakhalin.gov.ru

•Upravdel.sakhalin.gov.ru - Anonymous hacks tass.ru, a Russian media channel, to display a pro-Ukrainian message.

- Anonymous splinter group Network Battalion 65 releases 40k files from the Russian Nuclear Safety Institute.

- Conti Ransomware group sides with the Russian government in a statement. Infighting is reported at Conti and one member leaks data about the group with the declaration: “Glory to the Ukraine.”

March 1st, 2022

- A group claiming to be from Liberland — a disputed territory between Croatia and Serbia — launches cyberattacks against Russia, releasing 200gb of emails.

- Several international hacking groups launch cyber operations against Russia in response to Ukraine’s plea.

- Anonymous offers over $50k worth of Bitcoin to each Russian soldier who surrenders their tank.

- Anonymous-affiliate accounts claim the Russian Army doesn’t use encrypted telecommunications. They publish a list of frequencies and encourage people to disrupt Russian communications.

- Data belonging to 120,000 Russian soldiers is leaked.

March 2nd, 2022

- Hackers target the Russian Nuclear Institute.

- People leak information about the war to Russians via Google Reviews.

- A Finnish cyber protest group hacks a Russian logistics center to display pro-Ukrainian images. The Russian center’s employees even joined the protest.

- Hackers attack Sputnik.com to display fake news. Headlines include "Vladimir Putin Announces Engagement to Alexander Lukashenko" and "Putin is a dickhead."

March 8th, 2022

- The websites of Russian ministries and agencies — including Russia’s Federal Penitentiary Service, Ministry of Energy, State Statistics Agency, and Culture Ministry — are hacked to display anti-war images.

March 10th, 2022

- Anonymous Ukraine breaches Roskomnadzor, Russia’s communications and mass media regulator, and releases 364,000 files. Some files show details of the Russian government’s media censorship.

March 11th, 2022

- Anonymous Germany accesses the systems of Rosneft Germany, a subsidiary of the Russian state-owned oil company Rosneft, to capture 20TB of data.

March 13th, 2022

- Anonymous hacker DepaixPorteur teases a massive data dump on Twitter “that’s gonna blow Russia away.”

March 17th, 2022

- A prominent Anonymous account claims the collective is “launching unprecedented attacks on the websites of Russian gov’t.”

March 20th, 2022

- Anonymous threatens to cyberattack any companies that don’t exit the Russian market.

- According to DepaixPorteur, Anonymous Strategic Support and #OpRedScare printed messages on hijacked printers in Russia. The messages countered Russian propaganda and gave instructions for bypassing the Russian government's censorship of the internet.

March 23rd, 2022

- Anonymous hacks the Central Bank of Russia, exposing more than 35,000 files over a 48-hour period.

Are People Profiting from Cyberattacks?

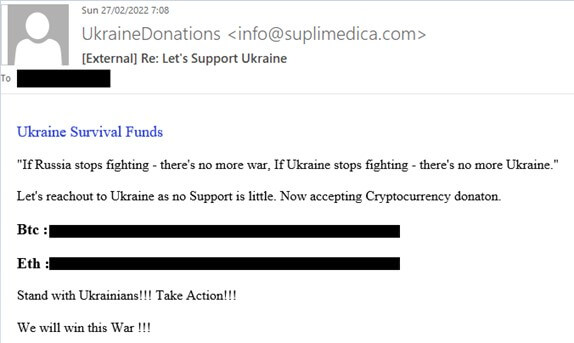

Cybercriminals are using the Russia-Ukraine conflict to scam people on both sides of the border. Security companies report a range of scams and phishing campaigns that exploit people’s desperation within Ukraine, and the willingness of others to help.

Security firm Check Point found a sevenfold increase in the number of phishing emails written in East Slavic languages at the start of the conflict. One-third of these messages originated in Ukraine and targeted Russian citizens.

Checkpoint provided an example of a phishing message, which convinced recipients to donate to a fake Ukrainian support fund.

A phishing message asking for donations to Ukraine

A phishing message asking for donations to Ukraine

Another scam appeared to target Ghanaian and Kenyan residents in Ukraine. A member of our own team in Kenya received a message, later proved to be a scam, that claimed to show the contact details and address of the office of Dr. Albert Kitcher, Ghana’s Honorary Consul to Ukraine. Kitcher later claimed scammers were exploiting the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and his office is only reachable via a separate number.

A scam asking Kenyan residents to contact a fake number

A scam asking Kenyan residents to contact a fake number

Individuals who are vulnerable, desperate, or exhibit generous tendencies become targets for scammers. Regrettably, we anticipate an increase in scams capitalizing on this crisis as long as it persists.

What Are the Risks of Cyberwarfare?

Russian cyber actions pose a threat to Ukraine's infrastructure. As we’ve mentioned, Russian efforts threaten to disable communication lines, sources of information, and civilian utilities.

Widespread Russian cyber tactics also pressure Ukraine’s defense. However, there’s no evidence of cyberattacks on a mass scale, and Ukraine is now putting up a strong cyber response. Pro-Ukrainian hackers are now disrupting Russian communication lines, institutions, and disinformation outlets. Theoretically, Ukraine could disarm Russia’s cyberwar with enough help from international hackers.

To date, Ukrainian institutions, websites, and services have returned to complete working order following Russian cyberattacks. These events are non-violent and temporary, which has limited their effect on the Ukrainian public so far.

However, Russian cyber aggression doesn’t just threaten Ukrainian cybersecurity. NATO leaders are concerned cyberwar will ultimately affect government institutions, infrastructure, and organizations around the world.

This concern isn’t unfounded. Western powers have imposed strict economic sanctions on Russia, and many nations expect Russian retaliation.

Both U.S. and U.K. officials have told businesses to stay alert to suspicious Russian activity. In Estonia, Prime Minister Kaja Kallas said European nations need to be “aware of the cybersecurity situation in their countries.”²⁷

Russia could be initiating cyberattacks against NATO members as we speak. Several U.S companies report increased levels of cyber probing — the first stages of a cyberattack. According to Rob Lee, the CEO of cybersecurity firm Dragos, Russian actors are behind a portion of these cyber probes.

“We have observed threat groups that have been attributed to the Russian government by U.S. government agencies performing reconnaissance against U.S. industrial infrastructure, including key electric and natural gas sites in recent months,”²⁸ said Lee, speaking to the Harvard Business Review.

And on March 21st, President Biden said that Russian actors were “exploring”²⁹ cyberattacks against the US, according to U.S. intelligence. Biden urged U.S. companies to take responsibility:

"You have the power, the capacity, and the responsibility to strengthen the cybersecurity and resilience of the critical services and technologies on which Americans rely. We need everyone to do their part"²⁹.

How to Protect Yourself?

What steps can you take to limit your vulnerability to cyberattacks and disinformation?

Here are some quick-fire tips to mitigate cyber risks:

- Use antivirus and antimalware software. Security programs can detect suspicious files and phishing attempts to protect your device.

- Use a VPN. These provide you with a secure, private connection to the internet.

- Use strong passwords. Use a combination of letters, numbers, and symbols. Update your passwords regularly.

- Use 2 Factor Authentication. This sends you a confirmation code via email or text whenever you sign into your account. 2FA removes the risk of hackers accessing your data using compromised passwords.

- Update your operating system regularly. New software updates often patch vulnerabilities that could allow an attacker into your device.

- Learn to spot phishing scams. Look for spelling mistakes in messages you receive. Don’t click a link unless you're 100% certain the source is legitimate.

- Remain skeptical. Don’t believe every piece of information you read or hear online. Cross reference articles with several other sources, and be especially careful about the information you share.

- Backup your data. You need to back up your most important files on both the cloud and a physical hard drive. Information such as your bank accounts and statements is considered important.

The Bottom Line

While we don’t know how this horrific conflict will end, cyberweapons are already playing a significant role. Russian hackers use cyber tactics to disable Ukrainian infrastructure, spread disinformation, and generally cause chaos among the Ukrainian people. However, we’re not seeing nearly as many Russian cyberattacks as analysts expected.

Meanwhile, with the help of hackers around the world, Ukraine is carrying out numerous cyber operations of its own. Pro-Ukrainian hackers are disrupting Russian communication lines and leaking Russian intelligence, and these information campaigns are an important part of Ukraine’s defense. These actions could disarm the Russian propaganda machine and build opposition to the war among Russian citizens.

Please, comment on how to improve this article. Your feedback matters!